In our column “Green space“

Christof Siemes, Anna Kemper, Oliver Fritsch and Stephan Reich take turns writing about the world of football and the world of football. This article is part of TIME on the weekendissue 8/2024.

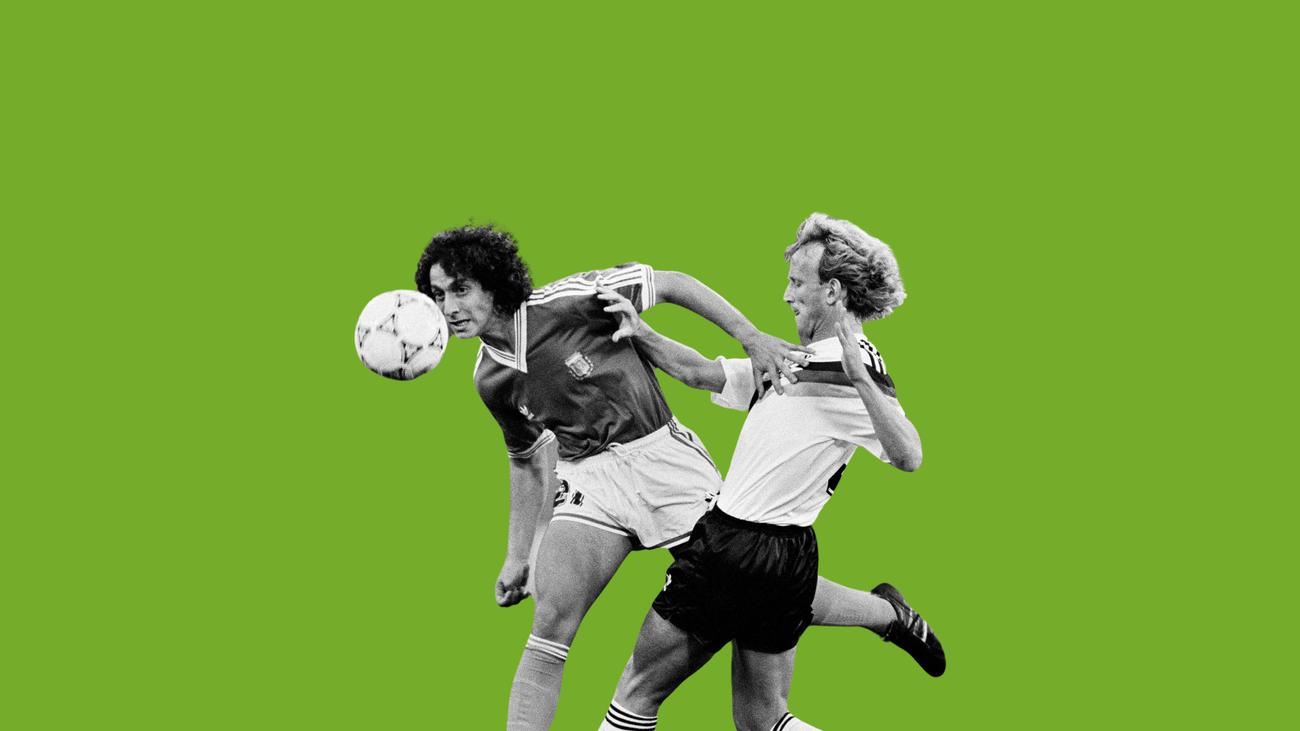

Given the occasion, we have to be a bit poetic and melancholic at this point. Andi Brehme was the first member of the 1990 World Cup team to die, much too early and only shortly after his team boss. Anyone who doesn’t stop there doesn’t have a football heart.

“If I have forgotten the last Goethe verse, I will still be able to list the Eimsbüttel storm,” wrote Walter Jens, the intellectual high-flyer of the old Federal Republic, in the ZEIT almost exactly 50 years ago. The memory of football moments is more lasting than all world literature. Peter Handke had already taken this idea to its extreme a few years earlier with his poem The line-up of 1. FC Nuremberg from January 27, 1968 is exactly that: the line-up of 1. FC Nürnberg from January 27, 1968, eleven names and the kick-off time. Of course that was meant to be a bit ironic, but it was and is true: football is pure poetry.

The football poem of my life goes like this:

The line-up of the German national team from July 8, 1990

Illgner

Augenthaler

Brehme Kohler Buchwald

Littbarski Matthäus Häßler Berthold

Klinsmann Völler

Game starts: 8 p.m

It had already been an amazing summer before the World Cup final and Brehme’s penalty. The wall had come down a few months earlier, and anything seemed possible. Even getting a ticket for a German World Cup game in Italy was not a question of luck in a multi-stage lottery. I simply went to a bus company in Freiburg, where I was studying at the time, and bought what today would probably be called a package: a bus ticket to Milan and a ticket for the preliminary round game against the United Arab Emirates for my father and me. This game wasn’t so important that it deserves its own poem; Stefan Reuter and Uwe Bein played instead of Kohler and Littbarski. But it was already a glimpse of the Roman finale, a glimpse of what might come.

Sometime in the morning we set off, almost exactly 400 kilometers south. The arrival at the stadium in Milan was overwhelming. San Siro was the first super arena of a new era; On the other hand, the Freiburg Dreisamstadion or my local Bökelberg were dollhouses. The eleven towers that held the new upper tier screwed themselves into the shimmering golden-blue southern sky, as if they were the cathedral in a Renaissance painting (the fact that it rained during the game does not cloud the memory in any way). Even my father, an old footballer who was there in Switzerland in 1954, experienced Pelé in Sweden in 1958 and saw Netzer coming out of the depths of the room during the legendary 3-1 win at Wembley in 1972, was moved by the beauty of that day.

Ten seconds after the kick-off at 9 p.m., Brehme is on the ball for the first time on the far left, stops it inimitable with his left, and then immediately circles it with his right in a perfect arc over to Berthold on the right. (I confess that I’m jog my memory with YouTube.) From then on he plays pass after pass, opening up space down the line or with a sharp cut into the penalty area, plus corners and free kicks, all as precise as if they came from a standardized game punching machine. Matthäus converts one of them directly from the edge of the penalty area to make it 3-1. Was it all easier back then? Or were they simply better than the 2024 squad?

We drove back that night. I saw the finale three weeks later in the company of a shared apartment in a stuffy attic apartment in Freiburg. Did I have confidence in Brehme when he ran up for the decisive penalty? His only gaze was on the ball, which I still consider to this day to be a sign of lack of self-confidence and not a good omen. But who am I to assume opinions about taking a penalty in the 85th minute of a World Cup final? Whoever scores is right. And the punching machine on his right foot didn’t let him down this time either and delivered perfectly fitting goods.

I learned in those happy days in the poetry seminar at university that a poem is the “selected ignition of the world in the subject”. In this sense, not only the team line-up from back then is a poem, but also Brehme’s shot: it always evokes in me the feeling of optimism from back then, when for a brief moment you believed that history had come to its end and everything would be okay . But with Beckenbauer’s howl of triumph that from now on they would be unbeatable for years to come, things took a turn for the worse. Brehme was never such a big talker. He wrote poetry and history, but only with his feet.

In our column “Green space“

Christof Siemes, Anna Kemper, Oliver Fritsch and Stephan Reich take turns writing about the world of football and the world of football. This article is part of TIME on the weekendissue 8/2024.

Given the occasion, we have to be a bit poetic and melancholic at this point. Andi Brehme was the first member of the 1990 World Cup team to die, much too early and only shortly after his team boss. Anyone who doesn’t stop there doesn’t have a football heart.

“If I have forgotten the last Goethe verse, I will still be able to list the Eimsbüttel storm,” wrote Walter Jens, the intellectual high-flyer of the old Federal Republic, in the ZEIT almost exactly 50 years ago. The memory of football moments is more lasting than all world literature. Peter Handke had already taken this idea to its extreme a few years earlier with his poem The line-up of 1. FC Nuremberg from January 27, 1968 is exactly that: the line-up of 1. FC Nürnberg from January 27, 1968, eleven names and the kick-off time. Of course that was meant to be a bit ironic, but it was and is true: football is pure poetry.