Jörg Schmadtke leans back, his hands cling to the back of his head. Thinking pose. Hmm, he mumbles, good question, he has never even thought about it: Who was there back then and who has stayed in the industry to this day? Michael Zorc determines, says Schmadtke, he’s been in Dortmund for half an eternity. Or Christian Heidel in Mainz, who is basically part of the inventory there. And, wait a minute: Wasn’t Klaus Allofs already in Bremen at the time?

Well, Schmadtke finally sums up, “there will be a handful, even if I can’t list them all now”. The head of sports at VfL Wolfsburg doesn’t want to put in any more effort, he says, that isn’t important at all. After all: The examples listed were correct, Messrs. Zorc, Heidel and Allofs were all already in office and dignity when Schmadtke took over his first job as sports director in 2001 at Alemannia Aachen.

Back then, however, the job was still called “Manager”; times were completely different. The tone was rougher, the manager the personified command center in the clubs. Not all of them behaved like a feudal lord, but almost all of them fulfilled the role of the strong man, whose right to exist today more and more people are questioning. And football itself was less complex, there were still no tipping sixes and only a few clubs with outsourced licensed player departments or corporations as investors.

So something has happened since Jörg Schmadtke, 57, hired in Aachen. Many of my colleagues from back then either lost time or failed to adapt to modern football. Schmadtke, on the other hand, was ennobled years ago as one of the best managers in the republic, by none other than Uli Hoeneß, and he should know, he has the best comparison with himself.

“People have their picture of me anyway. I don’t mind.”

Jörg Schmadtke is not only still there. He may be more successful than ever. VfL Wolfsburg has undergone an astonishing change: on Schmadtke’s first day at work in June 2018, the club, which was funded by Volkswagen, was still a near-second division, which had only been able to hold the class twice in a row via relegation. And then: Europa League, Europa League, Champions League.

On Tuesday, VfL scored a solid 0-0 in Lille in their first premier league game in five years, and the team is at the top of the table in the Bundesliga. Worth mentioning at this point: So far Schmadtke has maneuvered each of his clubs into a continental competition. In Aachen it was a football fairy tale, in Hannover 96 it was the result of serious development work. Then he went to 1. FC Köln, the only club that he really let himself into emotionally. Europe League. For the first time in 25 years.

Schmadtke left behind, at least that’s how some in the industry see it, but often also a heap of scorched earth.

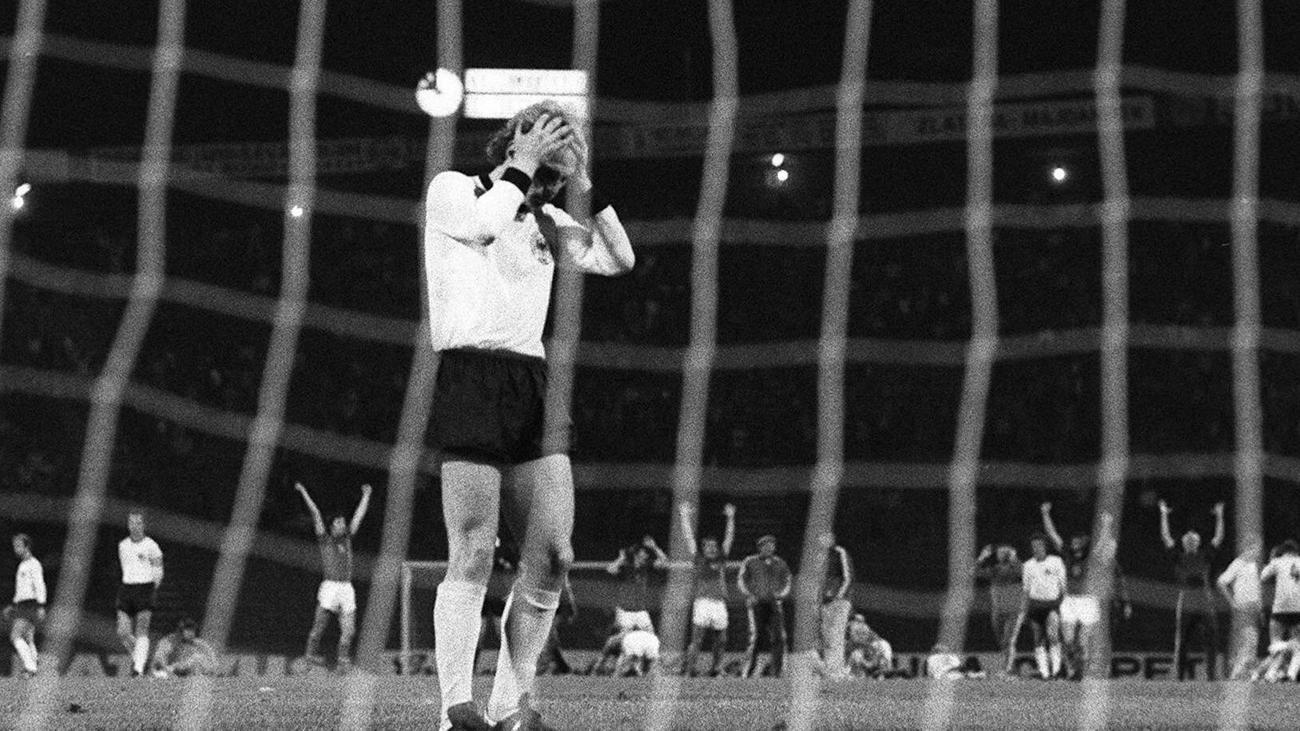

Football is also public image and communication, both of which are more important today than ever before. Schmadtke remained a mystery all these years. In a previous life he was an extroverted and humorous goalkeeper, he was considered an intellectual in a sometimes dull industry. The manager Schmadtke, on the other hand, has the image of the snotty sole ruler, who constantly signals that the football entertainment industry is pretty much on the pointer to him. He himself says: “People have a picture of me anyway, I can’t change that. But that doesn’t bother me.”

A day in summer, it’s hot outside, but in the VfL office, air conditioning and soft drinks ensure a pleasant atmosphere for conversation. Schmadtke wears casual trousers and a dark cardigan, and his mood is basically sporty and casual. If it weren’t for this suspicion, this supposedly open flank. His merits, all well and good, but so far, says Schmadtke, the public has mainly been interested in the matter with the coaches …

So he himself comes up with the topic that runs through his vita like chewing gum: Schmadtke has earned a reputation somewhere between Aachen and Wolfsburg for always finding the right coach for his teams, but unfortunately only rarely the right coach for a functioning sports director-coach relationship. So it was, for example, with the Austrian Oliver Glasner, who coached Wolfsburg to third place last season – and who now works for Eintracht Frankfurt, the opponent of VfL this Sunday (7.30 p.m.). This was also the case with Glasner’s predecessor Bruno Labbadia in Wolfsburg, or previously with Mirko Slomka in Hanover and Peter Stöger in Cologne: initially harmonious relationships that later ended in the divorce due to dissonances – either Schmadtke dropped out or the coaches fled City.

At 1. FC Köln, Jörg Schmadtke (left) and coach Peter Stöger had two found each other. In the end, Stöger was “totally surprised” by Schmadtkes Aus.

(Photo: Marius Becker / dpa)

Jörg Schmadtke attaches great importance to two statements. Firstly: In all these years he has only fired three coaches, a manageable rate that does not fit into the picture for the constantly mocking public. Second: In this job, says Schmadtke, the “most important thing is how one can superimpose individual interests and community interests”.

Perhaps at this point you have to sketch the impression that results from conversations with some of Schmadtke’s companions, people who worked closely with him or played football with him: Schmadtke never follows the wind, rather against it. In his private life he is a real cheerful person, only in public he goes to great lengths to hide it. He entered into conflicts because he carried out a deeper, more analytical, more far-sighted risk assessment than other sports directors; rather argue too early than too late. In a miraculous way, he manages to maintain a closeness to his players and yet remain aloof. He never acts out of vanity, but always for the benefit of the club.

Martin Kind, 77, the managing director of Hannover 96, tells something similar. In 2013, he was the first to witness a genuine Schmadtke trainer showdown, so to speak. On the phone, Kind says that his sports director at the time, Schmadtke, was “not in the mood for trench warfare” with 96 coach Slomka, that is the only reason Schmadtke made his position available at the time. Letting him go was “a big mistake” from the perspective of today’s second division team, Kind regrets. Schmadtke’s decision, on the other hand, testifies to “leadership strength”, he always thinks “employer-oriented”.

Do coaches have too much power today? Schmadtke wants to secure the decision-making authority in the club.

Interpersonal relationships ended in disputes for various reasons, but at the factual level it was always about the same: Schmadtke wanted to secure the decision-making authority internally, the coaches demanded more say in shaping the squad. So a very fundamental question was negotiated: Who sets the course for the sport? The club itself? Or a manager who may soon be a trainer somewhere else?

At many locations, the coaches have expanded their influence on strategic decisions over the past few years; they are increasingly determining what type of football a club plays. There may be reasons for that, in the event of failure, the coaches are still the first to lose their jobs. But many recently also have several consultants who manage their public relations work and place exit clauses in their contracts. The coaches have long been claiming the “next step” that players claim when they change clubs: Julian Nagelsmann went to FC Bayern with a million-dollar fee, Borussia Mönchengladbach lost Marco Rose to Borussia Dortmund and replaced Adi Hütter from Frankfurt Eintracht, which in turn obtained Glasner from Wolfsburg as a replacement.

Did he anticipate this development? Schmadtke says that he reacts “allergically” when a coach instrumentalizes “the media and the public” for his own interests, that “in the end always goes against the club”. It is like this: If a coach who is too influential disappears overnight, the entire construct could “get into trouble”. Indeed, some of his colleagues were presented with a fait accompli during the summer. The VfL sports director, on the other hand, was able to look around for a new coach for months while he was fighting with Glasner behind the scenes.

The “aggressive leader” is now training Wolfsburg: Mark van Bommel.

(Photo: Gabriel Boia / Eibner / Imago)

To everyone’s surprise, the choice fell on Mark van Bommel, 44, who has a trophy-rich playing career behind him, but as a coach could not yet show any great references. Many asked themselves: The former “Aggressive Leader” van Bommel and the alpha male Schmadtke – how long will it last?

So far it’s going well. When the Dutchman made a fateful mistake in the DFB Cup game in Münster and had to take scorn and malice for it and also the cup, Schmadtke demonstratively stood behind the new coach, whom he believes is exactly the right person to deal with VfL to reach the “next evolutionary stage”: more possession of the ball, faster solutions against low-level teams. Top team soccer. Schmadtke invested accordingly in the transfer summer: only FC Bayern has spent more money on new players.

His contract runs until 2022, extension not excluded

For the future of VfL, says Schmadtke, he has already designed a “storyboard”. He is building up the sports director Marcel Schäfer internally to his successor, they are now making decisions “on an equal footing,” he says. Schmadtke’s contract in Wolfsburg runs until summer 2022, but an extension cannot be ruled out. So in the end the question remains: does the industry really get on his nerves as it sometimes seems?

Jörg Schmadtke inflates his cheeks. For some protagonists in football, he says, “more differentiation in thinking” would not hurt. But actually he no longer feels like explaining his life to anyone.

.